Researchers from Technical University of Denmark, University of Copenhagen, University College London and partner institutions have developed a new type of brain implant that combines neural recording, light-based stimulation and targeted drug delivery in a single, ultra-thin device. The technology is known as the microfluidic Axialtrode (mAxialtrode).

The mAxialtrode is a needle-thin, flexible brain electrode designed to distribute multiple functional interfaces along its length. This allows researchers to simultaneously record neural signals, stimulate brain tissue with light and deliver medication at different depths in the brain. While the technology is currently aimed at basic neuroscience research, the developers see long-term potential for clinical applications, including the treatment of neurological disorders such as epilepsy.

More precise brain research

According to postdoctoral researcher Kunyang Sui, who led the development together with Associate Professor Christos Markos, the key innovation lies in combining several capabilities in a single, gentle implant. “Most current brain implants are made from hard materials like silicon, which can irritate brain tissue and trigger inflammation,” Sui said. “Our implant is made from soft, plastic-like optical fibers and has a specially angled tip that reduces damage during implantation.”

Traditional optical fibers used in neuroscience typically deliver light or record signals only at their distal tip, limiting measurements and stimulation to a single brain layer. This is a major drawback, as many brain functions, such as those involved in epilepsy, memory or decision-making, depend on interactions across multiple layers and regions.

Microfluidics and optics in one fiber

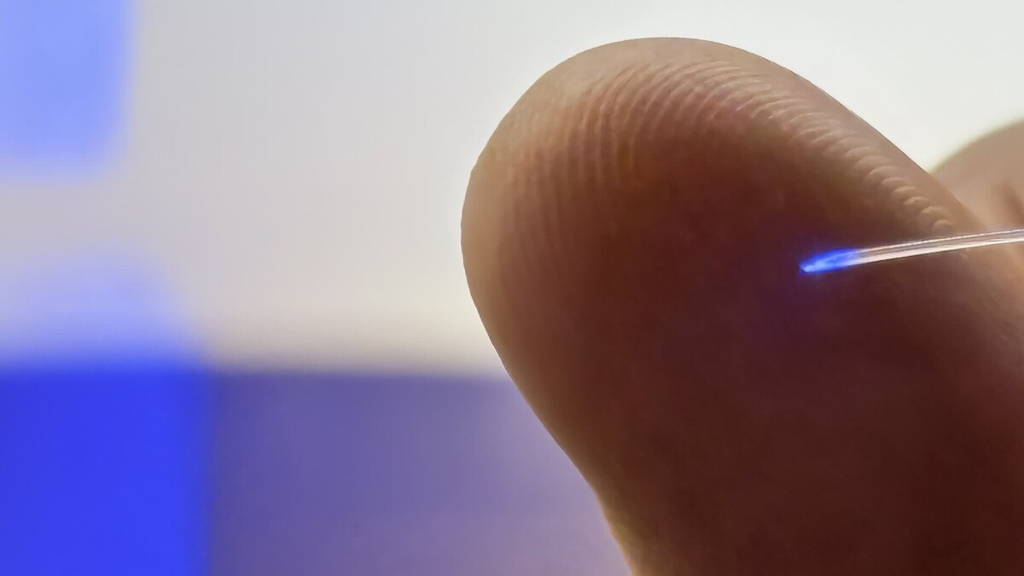

The mAxialtrode overcomes this limitation through its structure. Manufactured by heating and drawing a polymer rod into a thin fiber, the device contains a central light-guiding core surrounded by eight microscopic channels. These channels can transport fluids for drug delivery and house ultra-thin metal wires for electrical measurements.

The final fiber is less than half a millimeter thick and flexible enough to move with the brain, reducing long-term tissue stress. The technology is also described in the journal Advanced Science.

Validated in animal studies

The technology has been tested both in the lab and in vivo in mice. In these experiments, the implant enabled simultaneous optical stimulation with blue and red light, electrical recording from superficial and deep brain regions such as the cortex and hippocampus, and targeted injection of substances at multiple depths up to three millimeters apart. All functions were performed using a single lightweight fiber, without apparent discomfort for the animals.

The in vivo validation was conducted in collaboration with experts in neural circuitry and epilepsy models, including researchers from the University of Copenhagen and University College London.

Toward future clinical use

The research team is now working to patent the underlying technology and explore pathways toward clinical testing. Although extensive development and regulatory approval are still required, the mAxialtrode points toward a future in which brain implants are softer, more precise and capable of combining sensing and therapy in a single minimally invasive device.

Last year, researchers at ETH Zurich developed a magnetically controlled microrobot that can deliver medication with extreme precision inside the human body. Designed for minimally invasive therapies, the tiny robot can navigate through blood vessels and release drugs exactly at the site of disease, such as a blood clot in the brain or a tumour. Made from a dissolvable gel capsule embedded with iron oxide nanoparticles, the microrobot can be remotely steered using electromagnetic fields. Additional tantalum nanoparticles make it visible on X-ray imaging, allowing real-time tracking.

Once the robot reaches its target, a high-frequency magnetic field heats the nanoparticles, dissolving the capsule and releasing the medication locally. Published in Science, the research demonstrates a major step toward precision medicine, potentially reducing side effects associated with systemic drug delivery, particularly in conditions such as stroke where targeted treatment is critical.