Sleep trackers in the form of apps, smartwatches and rings are an integral part of the daily routine for millions of people. Devices such as the Apple Watch, Fitbit and Oura Ring promise insight into sleep quality, sleep phases and recovery. But experts emphasise that these technologies do not directly measure sleep. Instead, they derive sleep from signals such as heart rate and movement. This raises questions about the reliability of the data and how users should interpret the information.

The market for sleep trackers is growing rapidly. In the United States, it was worth approximately £4.5 billion in 2023, and revenue is expected to double by 2030. According to researchers, it is therefore essential that users understand what this technology can and cannot do for their health.

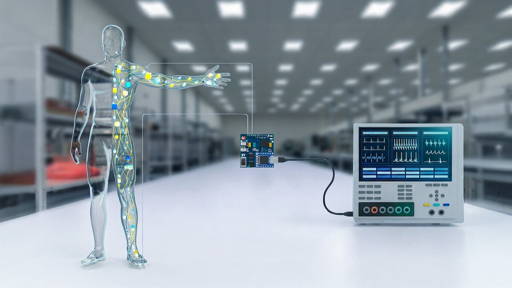

Indirect measurements, smart algorithms

According to Daniel Forger, professor of mathematics at the University of Michigan, most sleep trackers work on the same principle. They record movement and heart rate at rest and use algorithms to determine whether someone is asleep. These algorithms are now very accurate in determining when someone falls asleep and wakes up. Distinguishing between sleep phases, such as REM and non-REM sleep, is reasonably successful, but remains less accurate than sleep research in a specialised sleep lab.

According to Forger, anyone who wants to know exactly what their sleep architecture looks like is better off with clinical research. At the same time, he sees clear added value in wearables, precisely because they make sleep visible and discussable.

Focus on trends, not scores

Neurologist Chantale Branson of the Morehouse School of Medicine is seeing more and more patients in her practice who bring their sleep data to the consultation. The focus is often on details, such as the number of minutes of REM sleep in one specific night. According to her, this is not the right approach. Sleep trackers are particularly suitable for identifying trends over a longer period of time, not for drawing conclusions based on a single night.

Branson emphasises that wearables do not explain sleep problems. They do not advise why someone sleeps poorly and do not replace a clinical assessment. She advocates paying more attention to sleep hygiene, such as fixed bedtimes, less screen use before bedtime and a comfortable sleeping environment. Anyone concerned about their sleep would be better off consulting a healthcare professional first rather than investing in new technology.

Behavioural change as added value

At the same time, practical examples show that sleep data can contribute to healthier choices. Users recognise patterns, such as poorer sleep after alcohol consumption or late eating, and adjust their behaviour accordingly. In this sense, sleep trackers function as a feedback tool that stimulates awareness.

But there is also a downside. Some users become fixated on their sleep scores, a phenomenon known as “orthosomnia”. The urge to achieve a high score every night can cause stress and actually worsen sleep. Branson sees this mainly in people who compare their scores with others or set specific goals for sleep phases, while sleep needs vary greatly from person to person.

From insight to prediction

Forger expects that the greatest potential of wearables is yet to come. Ongoing research indicates that changes in sleep rhythms can be an early indicator of infections, depression or relapse in mental illness. Wearables can play a role in early detection and remote monitoring, especially in environments with limited access to care.

According to Forger, the technology is at the beginning of a broader development, in which a better understanding of sleep rhythms and sleep structure not only helps individual users, but can also contribute to prevention and personalised care. The key to this lies not in perfect measurements, but in the sensible and contextual use of the data.