Smartwatches that combine photoplethysmography (PPG) and electrocardiography (ECG) are proving to be a powerful tool in the early detection of heart rhythm disorders. New research from Amsterdam UMC shows that the use of an Apple Watch leads to a fourfold increase in the detection of atrial fibrillation compared with standard care.

Atrial fibrillation is the most common heart rhythm disorder and a major risk factor for stroke. Because symptoms are often intermittent or absent, the condition frequently goes undetected. Traditional ECG monitoring devices are effective but can be uncomfortable and are typically used for limited periods, often no longer than two weeks. “Conventional monitoring relies on external ECG devices, which patients may find irritating,” explains cardiologist Michiel Winter. “Smartwatches, on the other hand, allow for long-term monitoring in everyday life.”

Real-world evidence

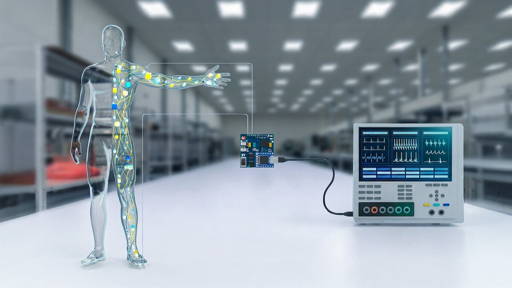

In the study, researchers analysed data from 437 patients aged 65 and older who were at increased risk of stroke. Of these, 219 participants received an Apple Watch and were asked to wear it for at least 12 hours a day over a six-month period. The remaining 218 patients received standard care. The smartwatch continuously monitored heart rhythm using both PPG and on-demand ECG measurements.

After six months, atrial fibrillation was diagnosed and treated in 21 patients in the smartwatch group, compared with just five patients in the standard care group. Notably, 57% of the smartwatch-detected cases were asymptomatic, while all patients diagnosed under standard care reported symptoms.

According to Nicole van Steijn, this real-world setting is key. “Wearables that combine pulse monitoring and ECG have existed for some time, but their effectiveness in screening high-risk patients outside controlled environments had not yet been thoroughly evaluated.”

Implications for care and prevention

The findings, presented at the annual meeting of the European Society of Cardiology and published in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology, suggest that smartwatches are not only suitable for long-term screening, but also significantly enhance diagnostic yield.

“By identifying patients who are unaware of their arrhythmia, smartwatches help speed up diagnosis and treatment,” says Winter. “This may ultimately reduce the risk of stroke. The health benefits, combined with potential cost savings from prevented complications, could outweigh the initial investment in the device.”

The study highlights how consumer wearables, when clinically validated and thoughtfully implemented, can play a meaningful role in preventive cardiology and data-driven, patient-centred care.

Smartwatch heart monitoring

Last year, researchers at University of Tampere developed a method that enabled the detection of congestive heart failure using data that can be collected by smartwatches. The approach, published in Heart Rhythm O2, analyses the time intervals between consecutive heartbeats using advanced time-series techniques. By examining complex patterns across different time scales, the method can distinguish congestive heart failure from both healthy heart rhythms and atrial fibrillation. Validation using international ECG databases showed an accuracy of around 90 percent.

Unlike other diagnostic approaches that rely on costly imaging such as cardiac ultrasound, the new method works with simple heart rate interval data. This makes screening possible with consumer-grade wearables, supporting earlier detection, more accessible monitoring and new opportunities for digital and self-managed cardiac care.