A major scientific breakthrough in antifreeze protein research could pave the way for significantly longer preservation of donor organs. Professor Ilja Voets has achieved promising results in developing new materials that prevent freezing damage in biological systems. Backed by a prestigious NWO Vici grant in 2024 and a recent European Research Council Proof of Concept award, her work aims to make long-term storage of donor organs for life-saving transplants a realistic possibility.

Voets, based at Eindhoven University of Technology, investigates how ice formation damages cells, tissues and organs, and how that damage can be prevented. Freezing biological material halts metabolism, theoretically allowing indefinite preservation. In practice, however, thawing often leads to cell death or loss of function. Ice crystals are a major cause of this so-called cryodamage, as they rupture cells and cause leakage of fluids.

Lessons from nature

Nature offers clues to overcoming this challenge. Arctic fish living in sub-zero waters do not freeze, despite having blood that is less salty than the surrounding seawater. Scientists discovered that these species produce ice-binding antifreeze proteins that prevent ice crystal growth. These proteins attach to ice surfaces, creating a curved, energetically unfavorable ice–water interface that strongly inhibits further ice formation, even at very low concentrations.

Inspired by this mechanism, Voets aims to understand precisely how such proteins work and how their properties can be replicated or improved. Ice-binding proteins are found across many species, including fish, insects, bacteria and plants, each using them in different ways to survive freezing conditions.

Designing new proteins with AI

Rather than isolating proteins from fish, Voets’ team produces them using bacteria in the lab. “In the chemical–biological laboratory of TU/e, we put bacteria to work to produce ice-binding proteins for us,” Voets explains. “That is not only better for the fish, but it also allows us to precisely modify protein structures to determine which elements are essential for their function.”

Together with researchers from Wageningen University & Research and Washington University, the team used artificial intelligence to design entirely new proteins with tailored properties. These artificial proteins are produced in E. coli and tested under different freezing conditions.

The collaboration recently reported its findings in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, describing a completely new family of synthetic antifreeze proteins. According to Voets, these proteins are more stable, more active and more versatile than their natural counterparts. “Naturally occurring ice-binding proteins are usually found only in cold environments,” she says. “Some lose their characteristic folding, and therefore their ice-binding ability, already at room temperature. The new proteins we developed remain stable across a much wider temperature range.”

Toward clinical and societal impact

That stability is crucial for real-world applications, such as organ preservation. “If you want to add such proteins to human donor organs before freezing, it helps enormously if they remain functional without strict low-temperature handling,” Voets notes. “That simplifies logistics and reduces the need for specialized equipment.”

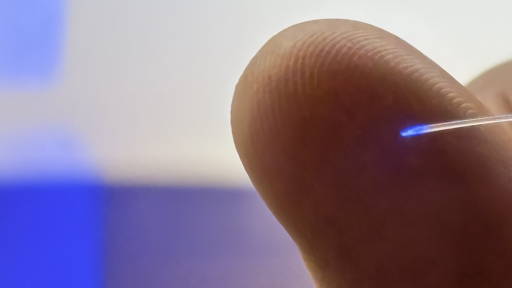

The breakthrough is the result of converging advances in protein design, cryobiology, soft-matter physics and microscopy. Using some of the world’s most powerful super-resolution fluorescence microscopes, Voets was the first researcher to visualize individual proteins interacting with ice at sub-zero temperatures. The work also involves close collaboration with biomedical engineers, cardiologists at University Medical Center Utrecht, and transplant surgeons at University Medical Center Groningen.

A next step toward large-scale impact came from postdoctoral researcher Tim Hogervorst, who showed that the key properties of these proteins can be transferred to polymer-based materials. This opens the door to scalable, cost-efficient production.

With support from innovation hub The Gate and the €150,000 ERC Proof of Concept grant, Voets’ team is now exploring how the discovery can be translated into a practical product. Ultimately, the goal is clear: reliable, high-quality preservation of tissues and donor organs, with potentially transformative impact on transplantation medicine.