A living, cell-based implant that functions as an autonomous artificial pancreas could significantly reduce, or potentially eliminate, the need for daily insulin injections for people with diabetes. That is the conclusion of a new study led by Shady Farah at the Technion Israel Institute of Technology, in close collaboration with Massachusetts Institute of Technology and several leading U.S. research institutions.

The research introduces a novel “living implant” that continuously senses blood-glucose levels and responds by producing and releasing insulin from within the body itself. Unlike current diabetes technologies, such as insulin injections, pumps or closed-loop glucose monitoring systems, this implant operates entirely on its own. Once implanted, no external devices, refills or patient intervention are required.

A living, self-regulating therapy

At the core of the innovation is a population of insulin-producing cells that behave like a biological sensor-actuator system. When glucose levels rise, the cells respond by generating insulin and releasing exactly the amount needed to restore balance. When glucose levels fall, insulin production automatically decreases. In effect, the implant acts as a self-regulating, drug-manufacturing organ.

What makes the approach particularly notable is its long-term stability. Cell-based therapies for diabetes have been explored for decades, but their clinical success has been limited by immune rejection. The body typically recognizes implanted cells as foreign, triggering an immune response that destroys them or severely limits their function.

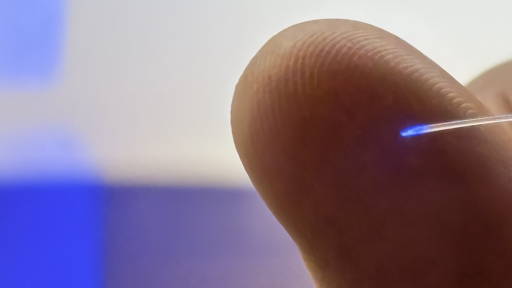

Crystalline shield

The research team addressed this challenge by developing a protective strategy they call a “crystalline shield.” This consists of engineered therapeutic crystals that physically and biologically shield the implanted cells from the immune system, preventing immune cells from recognizing and attacking them. At the same time, the shield allows glucose, insulin and other small molecules to pass freely, enabling normal metabolic function.

According to the researchers, this approach allows the implant to function reliably and continuously for several years. An essential requirement for any therapy intended to replace lifelong daily treatment. The findings have been published in Science Translational Medicine.

Promising preclinical results

The technology has already been tested in multiple preclinical models. In mice, the implant demonstrated effective, long-term regulation of blood-glucose levels without the need for additional insulin therapy. In non-human primates, studies focused on cell viability and functional performance confirmed that the protected cells remained alive and responsive over extended periods.

These results are widely regarded as a critical milestone in the path toward human application. While clinical trials in people have not yet begun, the combination of glucose control, durability and immune protection provides strong proof of concept

The origins of the technology date back to 2018, when Farah began developing the concept during his postdoctoral fellowship at MIT and Boston Children’s Hospital/Harvard Medical School. There, he worked under the supervision of Daniel Anderson and Robert Langer, a pioneer in drug delivery and tissue engineering and a co-founder of Moderna. Today, the work continues in Farah’s laboratory at the Technion, supported by an international collaboration involving Harvard University, Johns Hopkins University, the University of Massachusetts and Boston Children’s Hospital.

Beyond diabetes

Although diabetes is the immediate focus, the researchers stress that the underlying platform has much broader potential. The same implantable, closed-loop approach could be adapted for chronic conditions that require continuous delivery of biological therapeutics, such as hemophilia, enzyme deficiencies, and certain metabolic or genetic disorders.

If successfully translated to the clinic, the technology could represent a fundamental shift in chronic disease management, from repeated dosing and external devices to living, self-regulating therapies that operate seamlessly from within the body. For patients, that could mean fewer daily burdens, improved disease control and a markedly better quality of life.

Safer insulin dosing

Last year, researchers at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai developed an AI-based decision support model called GLUCOSE to assist physicians in safely dosing insulin for ICU patients recovering from heart surgery. Managing blood glucose levels in this setting is challenging, as both high and low levels can cause serious complications. GLUCOSE uses reinforcement learning to analyze large volumes of real ICU data and generate personalized insulin dosing recommendations in real time.

In evaluations, the model performed as well as, and in some cases better than, experienced intensivists, despite having no access to patients’ full medical histories. According to the researchers, the tool demonstrates how AI can enhance clinical decision-making in complex environments like the ICU. Published in Nature, the study suggests that data-driven AI support could improve safety and outcomes when applied responsibly in critical care settings.