Chronic wounds are a growing problem in healthcare, partly due to an ageing population and the increasing number of people with diabetes. For some of these patients, a poorly healing wound ultimately leads to amputation. Researchers at the University of California, Riverside (UC Riverside) have now developed an innovative oxygen gel that may prevent this scenario.

Wounds that do not heal within a month are considered chronic. Worldwide, this affects an estimated 12 million people per year. In approximately one in five patients, this ultimately leads to amputation. According to the researchers, oxygen deficiency in the deeper layers of the damaged tissue is at the root of many of these problems. Without sufficient oxygen, a wound remains stuck in a prolonged inflammatory phase, bacteria have free rein, and degradation occurs instead of repair.

‘Chronic wounds do not heal on their own,’ says Iman Noshadi, associate professor of bioengineering and leader of the research. ‘Wound healing involves multiple phases, from inflammation to regeneration. A stable oxygen supply is crucial in all these steps.’

Local oxygen factory

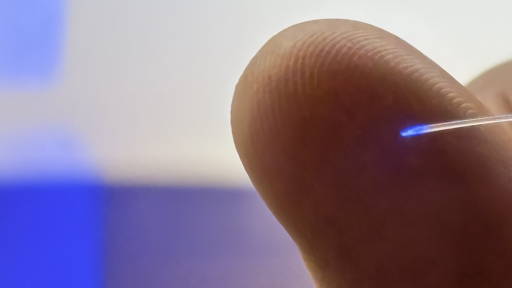

The gel developed addresses this problem directly. The soft, flexible material consists of water and a choline-based liquid that is antibacterial, non-toxic and biocompatible. In combination with a small battery, similar to those used in hearing aids, the gel functions as a mini electrochemical oxygen factory. By splitting water molecules, it creates a continuous and controlled release of oxygen.

Unlike existing therapies, which mainly deliver oxygen to the wound surface, the gel moulds itself to the unique shape of the wound. As a result, oxygen reaches precisely those areas where the deficiency is greatest and the risk of infection is highest. In addition, the oxygen supply lasts for up to a month, which is essential because new blood vessel formation often takes weeks.

Promising preclinical results

In animal models with older and diabetic mice, which closely resemble chronic wounds in humans, the effect was significant. Untreated wounds did not heal and were often fatal. With the oxygen gel, which was replaced weekly, the wounds closed within approximately 23 days and the animals survived. ‘This could develop into a product where the gel is renewed periodically,’ says PhD student Prince David Okoro, co-author of the study.

The chemical composition offers an additional advantage: choline helps regulate the immune system and inhibit excessive inflammation. This restores a better balance in the wound environment, rather than causing additional stress.

Beyond wound care

The researchers also see opportunities beyond wound care. Oxygen and nutrient deficiencies are a major challenge in tissue and organ cultivation. ‘As tissues become thicker, cells die due to lack of oxygen,’ says Noshadi. ‘This technology could be an important step towards the sustainable growth of larger tissues or organs.’

Although not all causes of chronic wounds can be solved with technology, the researchers believe that this oxygen gel offers a real opportunity to reduce amputations and significantly improve patients' quality of life.

AI model for better wound care

Last year, researchers developed a-Heal, an innovative wearable system that actively monitors and accelerates wound healing. The device combines AI, bioelectronics and a built-in camera and is attached to a standard bandage. Every two hours, an AI model analyses wound images and compares them with an optimal healing timeline.

When recovery lags behind, the system automatically intervenes with targeted therapies, such as local administration of fluoxetine or gentle bio-electrical stimulation to promote cell migration. This closed-loop system continuously adapts the treatment to the individual patient. Preclinical results show that wounds treated with a-Heal heal approximately 25 per cent faster than with standard care. In addition, telemonitoring enables remote care, reducing the burden on patients and healthcare providers.